Our karate practice must be specific to our needs. Ask 10 karate enthusiasts to describe their training and you just may get 10 different responses. Some karate-ka train solely for the exercise. Others value the pursuit of the perfection of technique, a practice I often refer to as kinesthetic poetry. Others prefer a competitive endeavour where they devote their efforts to the precise delivery of explosive ‘tag’ techniques in a rules-bound kumite match. When asked to describe karate, I always lean to its original purpose; self protection, which is the context I will use to describe `training scars` and how to prevent their formation. The training methodologies presented here are based on Iain Abernethy’s ‘Training Matrix’, experimentation, my experience with other martial arts and a healthy dose of common sense.

All Shotokan instructors have their strengths, weaknesses and biases which invariably show up in their teaching. Some will produce students who will go on to be kata champions or to master their kihon. I personally look at karate through a lens of practicality, something that is often lacking in the Shotokan world. Straightaway, let me state that by ‘practical’ I am not referring to the aesthetics of a yoko geri keage, the ‘snap’ generated by a quick gyaku zuki or the micro-corrections so many Shotokan practitioners obsess over in their pursuit of ‘perfect technique’. Seeking perfection of our karate form in this manner, although a noble goal in itself, does not necessarily lead to functionality because some of the criteria deemed to be desirable are for aesthetic purposes only. A practical approach to karate training for the purpose of self defense is something to which many mainstream Shotokan instructors give lip service at best. Many mistakenly regard fighting and self defense as the same thing. There are indeed some Shotokan practitioners that infuse their teaching with practical close range self defense oriented practices but they seem to be the minority. For those skeptical, threatened, or merely uninitiated in the field of practical karate, an open mind and a willingness to engage in critical self analysis is a must. I make these assertions not from the position of an authoritative figure but as a student of the martial arts who understands the value of objective self-critique and the difference between practicality and fallacy.

Like any other pursuit, the way we practice karate is important. When I was young, I went to a summer basketball camp. One of the coaches made a point which resonated with me to the extent that it has influenced my karate teaching today. Evidently, he must have been displeased with our efforts while performing some drills during an early August morning practice. I sat among my peer group on the parquet floor of the local college gymnasium as the coach stood, hands on hips, dramatically scanning the group of 12 yr olds before him. After a purposeful pause, he slowly uttered two words, carefully enunciating each syllable, “Practice…makes…”. Right on cue, we all shouted, “PERFECT!” completing his sentence for him. To our surprise, the coach lowered his eyes and shook his head. He collected his thoughts and explained, “No. Practice does not make perfect. Practice makes permanent.” Again, enunciating each syllable, he repeated himself. “Practice…makes…permanent”. I didn’t think much of it at the time as I wasn’t particularly enjoying the camp. Nonetheless, those three words permanently etched themselves somewhere in my deep recesses of my brain. His point was that if we practiced half-heartedly then we would play the same way but practicing with tenacity would make us a formidable opponent on the court. This concept has profound implications in our karate training but the scope is much more far-reaching than the need for intensity and effort in the dojo.

Before discussing layered training and training scars, it would be pertinent to establish some definitions that will be referenced later on.

Traditional karate

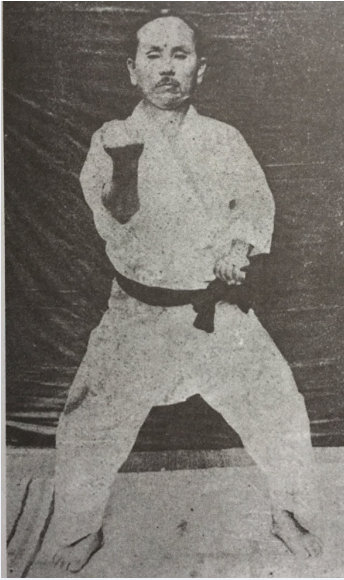

Most people who use the term ‘traditional’ to describe their Shotokan karate are practicing some sort of 3K syllabus (kata, kihon, kumite) as found in the JKA or one of its several splintered organizations. To describe mainstream Shotokan as traditional is ironic as the descriptor can be defined as ‘long-established’ or ‘time-honoured’. When I began Shotokan nearly 30 years ago, I was told that I was practicing ‘traditional karate’ when in fact it was a mere half century old based on its cosmetic appearance, training emphasis and syllabus. JKA-inspired Shotokan karate was developed post WWII by Master Nakayama and his contemporaries. It utilizes deep stances, long range attacks and large movements while strictly adhering to established criteria in the interest of creating movement with ‘proper’ form. I would argue that mainstream Shotokan practice completely lacks any functional use of grappling techniques. Though some instructors may include it in their teaching it is not in any of the syllabi of the major Shotokan organizations that I am aware of. Post WWII Shotokan was by and large born from a model which emphasized sport, recreation, athleticism and character development. It had long abandoned its gritty Okinawan roots. It is ‘form over function’. Despite my reservations on the label, I will use the term ‘traditional’ to describe mainstream Shotokan karate.

Those who follow a ‘practical’ karate model do so for the purpose of self defence. This is vastly different than the ‘traditional’ karate model described above. Practical karate, if taught correctly, must live up to it’s label. That is, it must be effective for protection against Habitual Acts of Physical Violence (HAPV). HAPV include haymakers, pushing, grabbing and anything else a person may encounter should they find themselves to be a target of civilian violence. This was the original purpose for karate training in Okinawa. Arguably, it is this model of karate that should be referred to as ‘traditional’.

Proponents of practical karate are more concerned with efficacy of techniques and are less inclined to concern themselves with cosmetic micro-corrections. Have you ever had a sensei move your fist 2 cm to bring it to your centerline? Or how about slightly raising your hikite so it is positioned 5 cm above your belt to some arbitrary standard imposed by the organization? Does it even matter? Practical karate is the polar opposite to traditional karate in that it values function over form. When striking a target, the goal is to hit hard while protecting yourself. For example, when using a reverse punch to strike a target there are essential fundamental movements that must be employed including hip and shoulder rotation and a transfer of mass forward into the target all while keeping your chin down and guard hand up to protect your face. Using a good hikite, keeping the spine perfectly vertical, holding the chin up and back heel on the floor are for aesthetics and are not given priority in a practical karate approach to developing a strong gyaku zuki. By focussing on effective technique, proper form is developed without obsessing on micro-corrections that have no functional purpose. With this approach, form follows function.

Habits are truly powerful. They are an essential part of human evolution that have allowed us as a species to survive over the last couple hundred millenia. Habits are formed as a result of repeated actions. For our ancestors, repeated actions resulted in favourable outcomes, reinforced with a release of neurotransmitters to elicit feelings of euphoria, calmness or other pleasurable emotions. By their very nature, repeated actions eventually become automatic and do not require conscious thought to execute. I first heard of the term, training scar at a practical karate seminar to describe dangerous habits that can result from flaws in our training. If not addressed in some manner, these flaws can ingrain bad habits that, despite our best efforts, can jeopardize our safety when confronted with civilian violence. These bad habits can cause us to automatically initiate a response to a violent confrontation in a less than optimal fashion. Proponents of practical karate are interested in conditioning effective responses, both physical and non-physical, that will keep targets of civilian violence safe whether the target(s) of the assailant be ourselves or others we are trying to protect. Many practitioners of practical karate also advocate non-physical skills such as scene awareness and verbal de-escalation. For the purpose of this article, I will not be discussing these skills but instead will focus on actual physical altercations.

All karate training is to some degree, unrealistic by necessity. To be completely true to ‘real world’ scenarios, we need aggressive, unpredictable and resistant training partners who are trying to harm us. In turn, we must have the same objective. In practice, each person must try to hit, throw, lock joints and choke with the goals of knocking out, slamming with force, break joints and choke to unconsciousness. Skin-touch punches, the use of tatami mats and allowing our uke to ‘tap out’ removes us from reality. Such flaws in our training, if left unchecked, can lead to the development of ‘training scars’, or the formation of bad habits that will surface in an emergency. For obvious safety reasons, training flaws are an essential component of our training, otherwise the dojo will soon be empty other than one remaining alpha warrior.

Layers of training

A layer is a component of our training that has its inherent strengths and weaknesses. Kata training is one layer common to all Shotokan dojos as is shiai kumite. Other layers include flow drills and pad work. All serve a purpose but have serious limitations.

Why are training scars dangerous?

In the chaos of violent confrontations, our bodies undergo a physiological response commonly known as ‘fight or flight’. Pupils dilate to allow more light to enter the eyes, blood vessels dilate to divert more blood to large muscle groups, tidal volume of the the lungs increases to aid in gas exchange, glucose is mobilized from the liver’s glycogen stores and cardiac output increases to maximize oxygen and nutrient delivery to muscles.

While our bodies will prepare for a potentially violent confrontation, our ability to think clearly in response to the stimuli before us is severely diminished. Despite what Carrie Underwood may have to say, Jesus won’t be there to ‘take the wheel’ when all hell breaks loose but for better or for worse, our training sure will! We will, by default, respond according to the way we train. Assuming we react to protect ourselves and not freeze (an unfortunate possibility), the neural connections in our brains created by repetitive actions in the dojo will take over. If we have not trained to address training scars in the dojo we will likely find ourselves victim rather than victor. In his classic Book of Five Rings, Miyamoto Musashi wrote that you can only fight the way you practice. This is sound advice for anyone invested in dealing with violent scenarios. Even in the 17th century, Miyamoto Musashi realized that practice makes permanent.

Pros and cons of various layers of training

Every type of training or drill we practice is, to some extent, unrealistic. On many occasions, Iain Abernethy has stated that all training is, by necessity, not real. Identifying the strengths, weaknesses and limitations of our training is the first step in avoiding scars. As difficult as it may be, it is essential that we check our egos and be critical of what we do. If a primary goal in karate training lies in self preservation, it is essential that we take the time to educate ourselves and take action to eliminate training scars. Shotokan has always been aligned with the ‘do’ ethos more than the practicality of a ‘jutsu’ approach. Consequently, typical Shotokan dojo training is riddled with practices that develop habits that are counterproductive of efforts to develop applicable self defence skills. Let us examine some common layers of karate training analyze their benefits and flaws;

Shiai Kumite

Shiai kumite, or tournament kumite training has many benefits. For those who are athletic enough, it develops explosive speed, precision of targeting and mastery of distancing for long range ‘fighting’. That said, it is one of the most problematic practices found in traditional Shotokan. I realize that this statement is likely controversial to many readers. I believe there are inherent benefits in shiai kumite. I teach it and have competed for many years. Despite this, I came to the realization years ago that this simply cannot be the only type of sparring that we engage in as it is somewhat limited in developing self defence skills. Meant for competition, shiai kumite is a rules-bound engagement where two competitors try to score points by executing punches, strikes and kicks at their opponent. Contact is limited and the referee stops the match once a wazari or ippon is scored. When we train for these sorts of competitions, our training is severely flawed.

The absence of blows and that penetrate the target is perhaps the biggest training scar associated with shiai kumite. Those that limit their partner work to this format will develop two dangerous habits; they will not learn to ‘hit to harm’ nor they will they learn how to deal with attacks intended to hurt them. I realize that my critics will argue that shiai kumite can be rough which I will not refute as I have both inflicted and received significant injuries while competing. I’ve also won tournaments and walked away without so much as a bruise. That said, tournament point fighting is entirely different than an altercation on the street where an attacker intends to put you in the hospital or worse. After years of training that doesn’t address these flaws, it is quite possible that experienced karate-kas will be ineffective when they need to use their skills to defend themselves. A worst-case scenario will involve him ‘tagging’ and stopping after he ‘scores a point’.

Naturally, the rules will dictate the nature of a fight as it will shape a person’s strategies in an attempt to win a match. Techniques that are effective for the kumite ring are not necessarily sensible choices for self defence. Kumite competitors in the WKF utilize a lot of kicks because they are awarded more points. I recently watched the Karate Canada’s national championships. I saw countless competitors attempt lead leg hook kicks as their opponent charged in. One competitor was quite skilled at this particular technique and it was obvious that he had put in many hours perfecting it. It was flashy and won him matches but I seriously question it’s effectiveness against a real assailant in the absence of a referee. When I teach shiai kumite, I make sure my students understand why we are doing it as well as its benefits and limitations.

Another problem with stoppage in shiai kumite is the way it conditions the practitioner to stop attacking once a point is scored. The last thing a person should do once they land a strike is to stop attacking unless it is evident that their attacker is incapacitated. When dojo kumite training is modelled after a tournament format, this mental ‘abort mode’ becomes ingrained in our neural wiring. Even during casual after-class sparring, many karate-ka will land a punch or kick on target and then immediately stop and ‘reset’. Even the recipient of the technique may stop because subconsciously he or she knows his partner ‘scored a point’. This approach to sparring is proof of the dangers of too much shiai kumite.This reminds me of a meme I once saw online. The picture was of a father consoling his upset son. The caption read, “I scored a point…but he kept punching me”.

Another issue with shiai kumite are the rules that determine permissible and prohibited techniques. In WTF Tae Kwon Do, punches to the head will generally not score. When they get too close to kick, they tend to push away to make distance again. I can’t think of a more flawed competitive format. Perhaps worse are the frequent attempts to land a jumping spin kick knowing that the referee will stop the match when they inevitably fall down.

In all Shotokan organizations that I can think of, clinching, grasping, choking, locks and strikes with the elbows and knees is prohibited in competition. These are banned for obvious safety reasons but create a problem. When competitors find themselves close together, the rules limit what they can do. In the WKF, you will often see two competitors find themselves face to face at close range, pause and agree to separate. They are conforming to the rules. Becoming conditioned to disengage at close range or lacking the skill set to deal with this range will get a person seriously hurt in a self defense scenario. This is an irrefutable fact as self defense encounters tend to occur at close range.

Kata

Despite what some karate purists insist, kata practice is not meant to teach you how to defend yourself. Thousands of repetitions is not the path to enlightenment, at least not as far as the combative meaning of kata is concerned. The great Gichin Funakoshi wrote, “Once a form has been learned, it must be practiced repeatedly until it can be applied in an emergency, for knowledge of just the sequence of a form in karate is useless”. Kata movements are far too formal and structured to decode without guidance of a knowledgeable mentor. The nonsensical bunkai often practiced in mainstream Shotokan is proof of this as kata is often applied ‘as is’ with rigid movements against traditional ‘karate’ attacks rather than against HAPV.

Perhaps equally discouraging is the realization that you will not be able to hit with devastating force when needed or with any degree of accuracy if you only practice kata. In short, kata on its own is of practically no benefit in learning to defend yourself. What a blasphemous declaration this must be for the purists reading these words! Despite the limitations of kata practice, it is an important layer in karate training. It has been said that without kata, there is no karate. I tend to agree with this sentiment. Patrick McCarthy has referred to kata as “…time capsules that were not originally developed to teach self-defence but rather to culminate the lessons already imparted.” Long before karate made its debut in Japan, kata was created by fighters for fighters. There was an assumption that a student already had an understanding of the nature of violence and how to protect themselves against it. Kata can be thought of as a kinesthetic encyclopedia; a means to document combative strategies to protect us from civilian violence but its usefulness hinges on our ability to unlock its meaning.

Let me be clear. It is true that Shotokan kata can train us to move with the speed and explosiveness needed to inflict devastation to an assailant. No, I’m not contradicting myself. Kata training must be coupled with other layers of practice including pad work and partner drills. Kata is only one of several essential layers in a comprehensive training regimine. Without actually hitting solid objects we will never understand the differences in biomechanics between moving our limbs through air versus movement into a target. Also, without a training partner, we will never acquire the subtleties involved in striking and grappling applications that is impossible to address with solo practice.

Stephan Kesting, a popular jiu jitsu practitioner with a kung fu background equates kata practice to learning how to swim on dry land. I encourage you to watch Stephan Kesting’s YouTube video, “Why kung fu forms and karate kata are (mostly) pretty useless”. He definitely ruffles a few feathers with his opinions but he raises a lot of valid points that may resonate with open-minded traditionalists.

Contextual Kata

Today, our practice is backwards; we learn the kata then we study the principles buried within. Once a person learns the oyo, or applications of kata, he or she can begin to visualize an imaginary opponent and practice what I call contextual kata. In this layer of training, one moves without the rigid stops and formalities found in typical kata practice. Height and posture can vary as needed to trap limbs, avoid danger, throw, and off-balance an imaginary attacker. Nakasone wrote, “Do not get shackled by the rituals of kata. Instead, transcend kata moving according to the strengths and weaknesses of your opponent.” I love this quotation as it gives us permission to take creative liberties in attempting to reverse-engineer kata. We can practice the spin into the final manji uke of heian godan as clearing an arm and moving in for takedown, or the opening movement in bassai dai as a guillotine choke. We do this all while altering our posture to protect our head or throw and using our hikite to pull a limb to a prefered position. When practicing kata this way, I prefer to move swiftly and fluidly without the ridgid stops we find in kata. My stance is higher, I don’t use kime at the end of my technique and I alter the techniques to make them true to the applications. For example, when I use oi zuki, my punch will finish before my foot does so it’s more like walking through a gyaku zuki. This allows me to hit then get close for a throw or clinch. This won’t get you past the opening round in your regional karate tournament but it is meaningful practice.

While I do not profess to be an leading expert in the area of practical karate, I assert that the vast majority of Shotokan instructors do not understand the true value of kata. They may advocate the practice of kata and claim that it will help one’s kumite or that you will come to understand its meaning in time. This is nonsense and nothing more than lip service. Worse yet, such statements may be meant to cover up their own lack of knowledge. Until one is specifically taught the principles that are encoded in kata, true understanding of its meaning will never be acquired. Only then can contextual kata be practiced.

Despite the invaluable benefits of kata in documenting self defense techniques, practicing kata alone without context ingrains awful training scars. When a student, especially one with many years of experience, starts to learn practical kata oyo for the first time, they move in a robotic, mechanical way like they would when performing kata. I know this from experience as I have taught classes in practical karate for black belts who have a decade or more experience in 3K karate. They struggle because they don’t know how to apply the simplest kata movements at close range, as they were intended. They struggle to break free of the shackles Master Funakoshi was referring to. Contextual kata practice will help remove this scar. It helps us heed Nakasone’s advice “…transcend kata and move according to the strengths and weaknesses of your opponent”.

Kihon

Kihon can be defined as fundamentals. In Shotokan, kihon consists of solo drills that allow students to practice various karate techniques. After the introduction of karate to Japan, kihon evolved as a means to accommodate a large number of participants in crowded dojos and is now an integral part of traditional Shotokan dojo training and grading syllabi. The benefit of Shotokan kihon is that it offers an opportunity to work on form with the explosiveness that Shotokan is known for and like kata, there is no training partner so it can be done safely.

Traditional Shotokan kihon presents a problem, however. The emphasis is on form rather than function. If one critically examines the combinations found in many grading syllabi, they are not designed for combat. They are somewhat nonsensical from a practicality standpoint. As is the case for kata, ‘proper’ form includes achieving standardized geometric configurations during and at the end of each technique that conform to specific aesthetically-based criteria including; a strong hikite, proper foot position (specific orientation and with heel on floor), and knee and hip orientation of stances etc. Many of the kihon combinations found in grading syllabi have no functional use. Consider this combination; step back shuto uke, mae ashi mae geri, gyaku zuki (stay in kokutsu dachi) all while moving backwards in a straight line. The necessity of utilizing long deep stances, large movements, an erect posture and other criteria in the name of aesthetics make most of our kihon dysfunctional. It’s for the sole purpose of general body movement.

When I am about to teach a new partner drill or padwork combination I will sometimes run through a solo version first. This version of kihon, however doesn’t have to conform to typical the aesthetic standards of kihon but it has to be functional. We mimic reality; we tuck the chin, allow our heels to rise as needed as our mass moves forward, and we keep the guard hand up when punching (no hikite) unless it is controlling a limb. The combination is drilled with speed and is later applied in partner drills to add context. This is contextual kihon.

Regardless of the type of kihon practiced, traditional or functional, they both leave obvious scars. Without a partner, we cannot get the feeling of manipulating limbs or using our weight to off-balance or striking a head or body. We also cannot get a feel for distance or learn to react to an opponent.

Layering training methodologies to eliminate scars

Pad Work

Some people go so far as to say that hitting pads, bags or a makiwara is useless because they don’t hit back. Striking pads with punches, hammer fists, forearms, shins, knees etc is an absolute must. As I mentioned previously, the mechanics of a traditional karate punch in air are much different than those needed to penetrate an actual target yet many karate-ka do very little pad work. Many sensei at seminars will spend an entire weekend teaching proper mechanics of ‘hip vibration’, hip rotation, sega tande other concepts all while throwing techniques through thin air. Many of the concepts taught may be valid to some extent but I’d argue that they are geared towards aesthetics rather than for efficacy.

I teach pad work on a regular basis in my dojo. I have seen dan ranks try to hit a focus mitt only to be disappointed in the feedback they receive or when their wrist buckles. If we never hit anything we will never know if our technique is effective.

Flow Drills

I absolutely love flow drills and see them as an essential layer of karate training. Flow drills take many forms and are great for ingraining muscle memory and useful habits by linking a series of techniques in a fluid manner and offer lots of practice in a short amount of time. The techniques can be strikes, locks, grabs, releases, chokes or throws or even groundwork. Some such drills have a designated tori and uke. Others will loop so they do not have a defined finish. Another format allows both participants to take turns being the tori/uke. A flow drill requires some degree of compliance from the uke. Although it is not uncommon for the uke to be fully compliant, my favorite format is where the drill has built-in resistance. The uke (person receiving the technique from the tori) blocks the tori’s strike, reverses a lock or stuffs a throw. Integrating these gyaku waza, or reversal techniques into flow drills are very valuable learning opportunities.

A well designed flow drill have many advantages. I enjoy designing drills that incorporate predictable responses from the uke. Such a drill is designed to force the tori to respond to failure and initiate another attack. Such carefully designed drills condition the practitioner to react in a manner to stay in control of an altercation. Recently, I have taken up Gracie jiu jitsu. I recently got caught in a standing guillotine. Without hesitation, I (gently) grabbed my training partner’s testicles which immediately prompted him to release his death grip to grab my wrist. This allowed me to easily escape his choke. My partner was shocked at what happened but we had a good laugh as Gracie jiu jitsu is more about self defense than sport.

An example of a looping flow drill that incorporates gyaku waza.

Despite the numerous benefits of flow drills, like anything else they are not without their flaws. The amount of resistance you can include in a flow drill is limited. Also, by their very nature, flow drills are a choreographed series of techniques. This does not allow for freedom of movement where you have to adjust to an unpredictable partner.

Iain Abernethy once told me that once we get good at a drill it’s time to break from the drill. Although getting a good flow is important and something we should strive for, it is not the end goal. If we really want to be able to protect ourselves we need to be able to apply techniques in a live environment against a non-compliant hence the need for live training.

Live Training

Live simply means that both participants are free to move as they wish. Depending on the goal to be achieved, this sort of training can be completely free in nature where participants are allowed to punch, kick, strike, throw, lock, choke and go to the ground if they so choose. Alternatively, the instructor may wish to limit which techniques are allowed. For example it may be desirable to eliminate long-range striking which would require participants to start in close range. If there are no mats to use, certain throws maybe prohibited in the interest of safety. Another interesting option is to give the two participants different parameters within which they must work. For example maybe partner ‘A’ is allowed to strike at long-range while partner ‘B’ must try to close a distance, clinch and go to the ground. One of my favorites is to allow one partner to do as they wish while the other is only allowed to throw wild (but controlled) haymakers.

Variety is important. We don’t want to get accustomed to sparring with martial artists all the time as they don’t attack like a street goon. We sometimes spar from our feet in the jiu jitsu gym I train at. I feel a bit at odds against a larger skilled opponent because I’m not allowed to strike but it helps me work on my grappling. If we are wearing gis I find myself defaulting to a traditional judo grip which the other students are unfamiliar with. If we are not wearing a gi I will have to clinch and be wary of the single leg takedown. I personally find this live training with restrictions to be extremely beneficial. It keeps you on your toes and forces you to work on things you may be less comfortable with.

Live training is an absolute must for anyone who is serious about honing their practical karate skills. That said, live training as with any other layer of training, is not without its flaws. We punch without hitting, ‘parachute’ our partners after throws, and we allow them to tap out if they’re being choked or locked.

An example of a layered drill

I am a firm believer that as instructors, we should ensure our students understand the purpose of what we teach in the dojo. I no longer subscribe to the Japanese “shut up and train” approach that I accepted years ago. When my students ask questions, I make it a rule to avoid answering using the word ‘just’; “It’s just for body movement”, “it’s just a drill” etc. When we answer questions in this manner it negates the importance of what we are teaching. That said, if we can’t come up with a functional reason for what we are teaching then maybe we should start questioning our teaching pedagogy.

Each layer in the flow drill outlined below has many benefits as as well as shortcomings. As instructors, it is important to understand this and educate our students on the nature of the unavoidable flaws of our training and the potential development of training scars, hence the need to layer training.

Layered drills are a great way to practice a series of techniques. Some may argue that this approach should be reserved for advanced students. To that, I would counter that such an opinion reveals a need to critically examine one’s teaching pedagogy. I firmly believe that even beginners should learn all karate has to offer at some level. They need to hit pads, engage in light sparring, throw, choke and lock joints in a safe environment that is appropriate to their level.

Below is an illustrated description of a layered drill. I like to spend at least an entire class on a drill of this length provided the core techniques have already been learned. Students should already have learned pad work, parrying punches, clearing limbs, a guillotine choke and basic throws. The layers described includes a two-person drill that includes predictable responses, contextual kihon and the same two person drill utilizing pads. Note that the predictable responses by the uke have been integrated which force the tori to flow into a backup plan. The drill has also been designed to help train the use of tactile sensation for locating body parts to be cleared or hit. A video breakdown of this layered drill is linked at the end of this article.

Layer #1 Two person drill

The benefits associated with this layer should be obvious. Training with a real person provides actual anatomy to punch towards and manipulate. As mentioned above, the design of this drill incorporates predictable responses from the uke. The kizami zuki fails so a hook (mawashi zuki) is thrown. The blocked hook allows us to practice using tactile sensation to locate and clear the uke’s left arm. We can find an actual head and throw an elbow towards it. Next, we get to apply a Thai clinch and throw a knee which should cause the uke’s hips to shift back, exposing the neck opening the door for a guillotine choke. The uke then simulates a testicle grab to escape from the choke which forces the tori to once again adjust. This flow drill solidifies a lot of great habits but the obvious flaw is that we can’t actually hurt our uke. Left unaddressed, this flaw can lead to a training scar as it teaches us not to hit or finish a choke etc.

Layer #2 Two person drill with pads

Pads are introduced in layer #2, which enables us to hit a real target. Unfortunately, in doing so we are replacing one flaw with another. There are different ways to work the geometric configuration of the initial targets but for me, it was a priority to preserve the opportunity to peel away the uke’s left arm which blocks the hook punch. To accommodate this in such a holistic drill, sacrifices were made in the positioning of the pads. They are sometimes in the wrong place; the head is in two places at once, the uke’s right hand is peeled instead of his left etc. Also, I don’t own heavy Thai pads so the elbow strike feels weak as it hits the lightweight pad as do the knee strikes. There are many reasons for configuring the padwork as I did but a written rationale would be rather cumbersome.

Layer #3 Contextual Kihon

Although this drill is kata-based, the best form of solo practice would be contextual kihon. Here, we get to move with uninhibited speed and work on footwork, functional posture, fluidity etc. Obviously this practice has limitations as there are no targets to hit nor is there an actual body to interact with.

In addition to the strengths and flaws already described in detail, it is important to understand what this drill is not meant to be; a prescribed fighting sequence. You are very unlikely to accomplish all the techniques against a resisting opponent nor would you want to for legal reasons. We should think of this type of exercise as a method to teach principles; dealing with failed techniques (when punches don’t meet their target); using tactile sensation to locate body parts; clearing limbs to create openings; responding to predicted responses etc. When watching YouTube videos of drills such as this the neanderthal keyboard warriors are quick to make their usual dim-witted, juvenile and uneducated comments, “That would never work”, “You’ll never pull off that throw in a street fight”, or “Why not just punch him in the throat?”, and my favorite, “I wish all my opponents were that compliant”. Boxers, judo-ka, MMA fighters and BJJ practitioners all do flow drills. In my jiu jitsu class, we do short flow drills; scissor sweep entry to arm bar entry (from guard) to triangle choke. I also recall doing some flow drills when I trained in judo a couple of years ago. Prearranged flow drills with compliant training partners represents a layer of training which is universal to all practically minded martial artists.

Layer #4

The three layers described above represent a regular part of my teaching pedagogy. Live training is another absolutely essential layer of training. Resistance is limited when doing drills for the sake of allowing the drill to flow. That said, we must regularly break free of drills to engage in live training. There is no point in being the dojo’s drill phenom with little ability to adapt during an unpredictable encounter. Here, through repeated failure against resisting opponents, we learn to adapt to resisting opponents and over time learn to take advantage of opportunities we stumble across or even opportunities that we purposefully create once we gain proficiency. To quote actor Will Smith but in a completely different context, “Fail often, but fail forward.” Let’s allow ourselves to fail in the dojo but learn to adapt in the process.

You may have guessed it already but live training is not without its flaws. Although injuries are a possibility, we can’t intentionally hurt our partner and so we may not get the predictable responses we are looking for when throwing knees, elbows etc.

Conclusion

It is imperative that we avoid one dimensional training, or the tendency to practice only one layer. Marching up and down the dojo doing line drills or ripping through 20 kata on any given night is a fantastic workout but, in my opinion, of limited value in developing self protection skills.

I often read and participate in online karate forms. One thing that baffles me is the crippling effect that a dogmatic approach has on our ability to grow our art. I frequently encounter ‘traditionalists’ who shun any approach to practical karate, especially if it comes with the ‘practical’ label. There are some karate practitioners who will insist that thousands of repetitions of doing kihon and kata will magically pay off should they ever need to defend themselves. One person criticized a Heian Shodan video I shot where I shifted my rear foot slightly in movement #4 to adjust my distance. His argument was that the shift was not in the kata so it wasn’t a legitimate application! Some argue that there are no grappling techniques in Shotokan despite the fact that our katas are full of throws, locks and chokes. Others will insist on defending against oi zuki attack when applying kata. It is unfortunate that there are so many people who refuse to evolve.

There is a growing movement in the western world to make karate practical again. The 3K approach, found in all major Shotokan syllabi that I know of is flawed, broken and needs to adapt to today’s critical internet-savvy world. A close friend of mine said that if we don’t soon change, “…we will not survive…and be relegated to teaching kids’ classes to pay the rent.” Let us not seek to preserve some ‘pure’ form of karate like some prehistoric mosquito in amber. That species has either gone extinct or has evolved to adapt to its changing environment. Likewise, we should allow karate to progress, improve and evolve.

In the interest of making karate practical as it was in the pre-Japan era, syllabi and teaching methodologies need to be reconsidered. Let’s start putting function before form. Master Funakoshi wrote, “Times change, the world changes and obviously so too must the martial arts change.” He was, of course talking about its change from a jutsu martial art to one for sport and recreation. I believe that perhaps it’s time that things come full circle.

Andy Allen

Special thanks to Alex Saunders, 5th kyu, for being my uke.

Photo credit, Ryan McGuire

Want more? Watch the video below for a complete breakdown of the drill described above!