Kihon is a Tool, Not a Goal!

Advocating a function over form approach in the name of practicality

By ANDY ALLEN

Basics, basics, basics! We’ve all heard that mantra, haven’t we? Often, senior karateka and their students will stress the importance of a solid foundation upon which to build effective karate techniques; good stances, snappy technique, correct posture and body alignment etc. Whilst I acknowledge that basics, or kihon, are important, I also believe that we need to be objective and think for ourselves rather than reciting what has been preached to us over the years ad nauseum. I would argue that kihon training has its benefits while at the same time is limited as a training tool. I doubt many would disagree with that but I could be wrong. I would also add that endless repetition of ‘traditional’ kihon can lead to bad habits. That’s the problem with a “form over function” approach to karate. Good kihon is a tool, not a goal. I will come back to this statement when I address the limitations of kihon, the problem with how it’s taught in traditional systems and how we can make it meaningful.

Before we explore this further, let me clearly define my perspective so that we are on the same page.

What are our goals for training?

The points I am about to outline may or may not resonate with you. That, in part, depends on your reasons for training. Drilling kihon while your sensei counts the reps and encourages you to push yourself is beneficial. “Faster! More spirit!”. Everyone yells “OSU!” and pummels those air molecules to oblivion.

I remember training with Koyama sensei 20+ years ago. He was teaching the technical points of a particular kihon combination. It was hot in the crowded dojo and we were all drenched in sweat as we worked through the drill. The theme was driving off the big toe to generate forward momentum. Then it was time to ramp things up. We powered through endless repetitions of that kihon combination. “Big toe!” Sensei encouraged us to remember the theme he was teaching. We were getting tired. “One more time!”, he would yell. 40+ black belts exploded through the air and ended combinations with thunderous kias! “One more time! Big toe!”, sensei yelled again. We complied. “One more time!”, he repeated. This went on for a long stretch of time to the point where even the most conditioned and determined black belts really started to fade. Finally, it ended and I think we all quietly congratulated ourselves for endeavoring through the hardship. Did we get a good workout? You bet! Were we challenged? Obviously. Did we try to perfect our technique? Yes again. Drive off that big toe! There are many benefits to this sort of training. As the dojo kun teaches us, it may even help us to endeavor when life is tough. Ken zen ichi. Mind and body as one.

But wait, does kihon alone help us become better fighters or more able to defend ourselves? The short answer is no. Kihon, and kata for that matter, will be of very little benefit if that’s all we do. They are merely one layer of training. My number one reason for practicing karate is to develop practical skills for fighting and self defense so my kihon must help achieve that goal. Good kihon is tool, not a goal. I think that’s worth repeating. Good kihon is a tool, not a goal.

“Traditional” kihon training is flawed

Let me define traditional kihon as what is done in the major Shotokan organizations around the world; long stances, use of hikite and strong kime etc. It surfaced sometime in the post WWII era when the popularity of karate exploded as an easy way to teach many people in a confined space. It also conformed to the ‘do’ model of Japanese martial arts. This type of training was not meant to develop combative skills, but rather to train the mind and body. It is important for us to consider the origins for any training methodology if we are to make claims of its usefulness. Let us consider this fact before we cry heresy at the thought of change.

There are a number of reasons why traditional kihon will lead to training scars (bad habits) if we want to develop functional skills. Note that I’m not saying that we should never train kihon in a traditional means, but in my opinion, it definitely should never make up a third of a class. There are too many other things to work on.

So, how can we make our kihon more meaningful in developing transferable skills? A good rule of thumb is that we should be able to directly apply kihon to partner work (not step sparring which also has its issues) including kumite, grappling or pad work. There is a huge disconnect between kata, kihon and kumite in 3K organizations despite the fact that they are often presented as parts of a whole. Over the years, I heard from many masters that practicing kata and kihon would make my kumite better. I didn’t understand it 30 years ago. Eventually, I came to realize that it was nothing more than lip service. Let’s look at some inherent flaws of traditional kihon and how we can correct them.

1. Hikite. At the risk of igniting another hikite debate, we should never pull an empty hand to our hip. It does not increase power. It does leave our face wide open. After 30 years of practicing hikite, I still struggle with keeping my guard up when sparring and doing pad work. It’s a bad habit I acquired from three decades of pulling my empty hands to my hips.

This is an easy fix. Don’t do it. Once I joined the World Combat Association, I had the freedom to change things as I pleased. Abandoning hikite in kihon was one of the first things I did. In my testing syllabus, most of my kihon is paired with pad work. Full disclosure; punching without using hikite isn’t going to feel as strong when punching in thin air. You don’t get that same feelings of tightness in the lats of your non-punching side. Just don’t mistake that for lack of power 😉.

2. Keeping the heel down. This as steadfast rule is just wrong and is probably worthy of its own discussion. Keeping the heel down is great for stability in grappling situations and perhaps close range striking. Dynamic striking requires dynamic movement which in turn is aided when the heel is allowed to raise off the floor. Remember my story about Koyama sensei’s class? BIG TOE!

There is a ‘test’ I have seen many instructors do. Someone stands in a reverse punch position with their back heel up. The instructor then applies a blow to their outstretched fist which causes them to wobble. They repeat the process with the heel down. The heel down provides more stability and the person doesn’t wobble. This is proof that we need to keep our heel down when a force is applied on our static body. It simply does not apply to a dynamic punch where the person’s mass moves into the target. A good striker can generate devastating power with his heel off the ground. A poor striker cannot.

When I am teaching kihon, I want students to develop an understanding of moving their mass into the target. I don’t spend a lot of time teaching a gyaku zuki in a stationary front stance. That will help teach rotation which is very important but it also ignores other principles of power generation such as weight transfer and forward movement of mass.

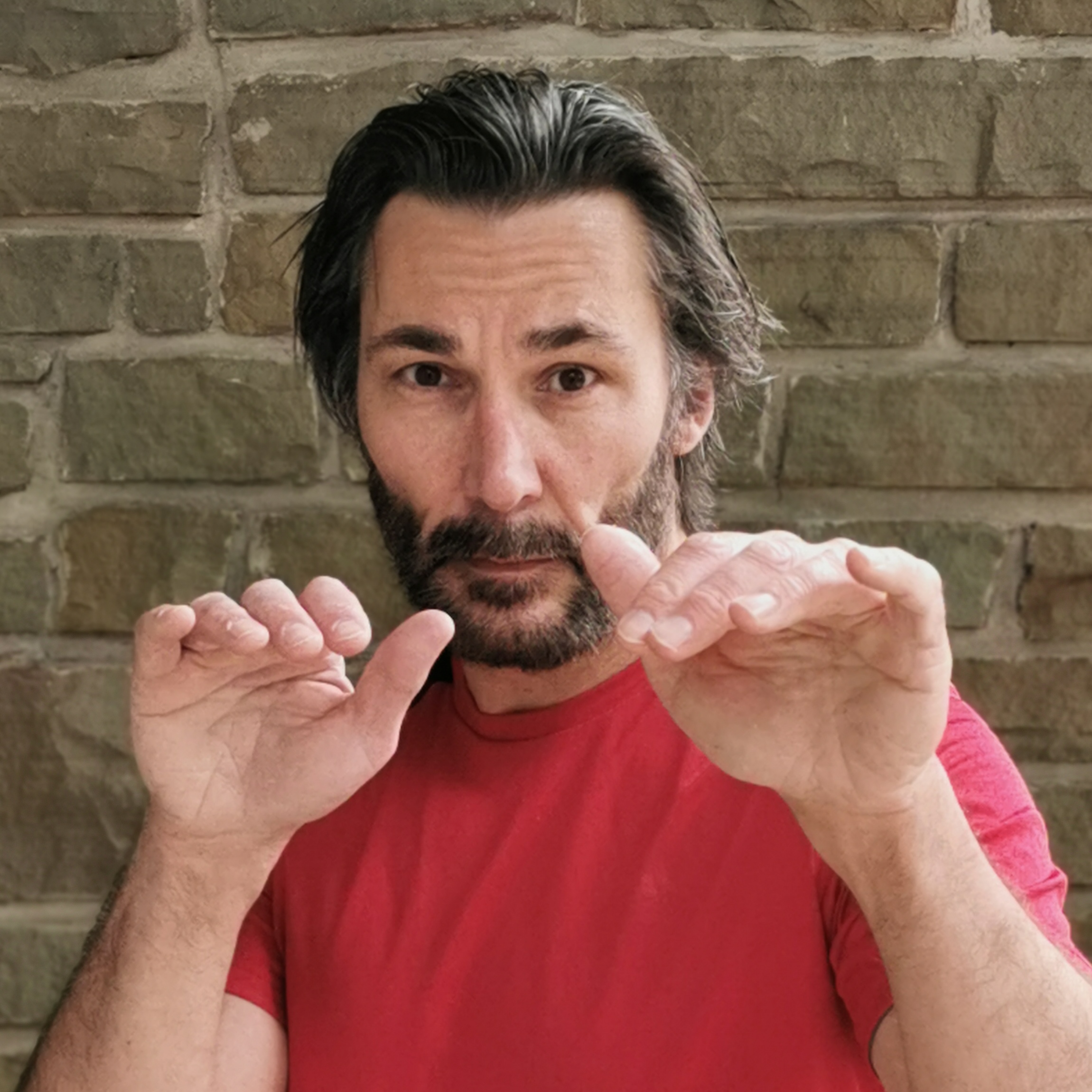

The author demonstrating the traditional “heel down” vs a more dynamic “heel up” posture.

3. Posture. Traditional kihon requires an erect posture with a vertical spine and the chin up. There is a reason for this. An erect posture allows us to focus on the hips and legs to generate power and to maintain balance. While this may be fine as a beginning stage for beginners, it simply is not a good idea to get into the habit of keeping your head up in the air when training. Musashi, the famous swordsman, famously said you can only fight the way you train.

I remember reading an interview with a Shotokan instructor. He frowned upon the trend of kumite competitors breaking the center-line when fighting and claimed that there was a certain nobility with maintaining an erect posture during kumite. Just take a minute to ponder that on your own.

This is actually a pretty easy fix for teaching new students. Just teach it differently. The trick is to make sure students are still utilizing good mechanics. They still need to rotate the hips and shoulders. As instructors, we need to ensure they are driving off the floor and moving their hips. Beginners will have a tendency to lurch forward with their shoulders while leaving their hips behind and dragging their rear leg. As instructors, we just need to correct that. The consequence of failing to break away from traditional kihon at an early stage in training is the development of training scars. Old habits are hard to break and I am living proof of it. As instructors, there is pressure to teach the grading-based kihon to prepare for tests. I see this as a problem of large organizations with outdated curricula. I am hopeful that one day they will change but I doubt it.

The author demonstrates good posture vs common mistakes made by beginners.

4. Long fixed stances and footwork. In most Shotokan dojos, a lot of time is invested in making “proper” stances, many of which are very long and deep. Move your knee out 2 cm, bend your knee 10 more degrees. Lower! The long stances of Shotokan were not Funakoshi’s doing. That was one of the changes his son, Gigō and his contemporaries made. Long stances make mobility difficult which is ironic considering stances are not really meant to be static. Consider them to be snapshots from movement. Often, senior instructors will justify the long, deep stances as a means to train your legs or that moving in long stances will make you better at moving from short stances. This may be true but I find the long stances are difficult for students to abandon when they it is time to move in a more functional way.

From my experience, students with a strict 3K background do not understand how to shuffle and move with their partner. They often leave their rear leg outstretched behind them in a long front stance when they need to have their feet closer together. Karate has many types footwork used in tai sabaki (body movement) including tsugi ashi and yori ashi but they tend do not appear in Shotokan syllibi for kyu ranks. My sensei used to do a lot of kihon that utilized creative types of footwork. It was sometimes void of context but over the years I discovered many ways to make use of it.

The author demonstrates how to use karate footwork to evade a kick and transition into a throw.

5. Lack of Fluidity. This point ties into the issue surrounding static stances. I have heard from many non-karate martial artists that we karateka are very stiff. This may be true to some extent. It is partly due to the nature of kihon (and kata). Some claim that the “stop motion” is to show “proper technique” but this is flawed thinking. We can’t claim that it’s to show proper technique because if you can’t fight like that then perhaps it’s not “correct”. Remember Musashi? He famously said, “You can only fight the way you train.” Perhaps, instead, we should train like we want to fight. Freezing after each movement to show “good technique” do not encourage fluidity of movement.

The kihon we see in Shotokan testing syllabi is very robotic. We explode into a technique, pause for a split second then continue to the next part of the combination. I think that to make kihon more meaningful it should be more fluid. Neither boxers nor Muay Thai fighters practice shadow boxing with the kind of “stop motion” that we see in karate. Nobody fights like that so why should we do it? It seems as though this “stop motion” sort of movement is unique to most form (kata)-based martial arts such as karate and tae kwon do. Kata is a very formalized practice and was never meant to teach us how to move in a physical encounter. (That’s another statement worthy of its own discussion). It’s like a kinesthetic mnemonic for defense against Habitual Acts of Physical Violence. I accept the formality of kata, but why does kihon need to be the same? I think kihon should be functional. Function should drive form. Read that again. Function should drive form.

Instead of the stop motion, I like to let the techniques flow together. It sometimes resembles shadow boxing. I know that this may be in contradiction to conventional wisdom found in Shotokan circles. Some may argue that it’s not “pure” karate. Remember, kihon is a tool, not a goal. Shotokan’s took is broken. Well, that’s only true if you share my goal of functional training.

For those who are into sport karate, you probably already do this. Let’s say you’re working on a combination; chudan gyaku zuki followed by a lead leg hook kick. You drill it in air for a few minutes then you do it with a partner. Then maybe you do it with pads for targeting. That’s what I call layering training. That’s all I’m doing but sport karate is not my targeted context so we don’t do hook kicks.

Fluid kihon needs to start from a natural fighting stance, not from a rigid front stance. Let’s consider a common kihon combination; kizami zuki, gyaku zuki (jab, cross). This is a pretty standard combo in all striking arts. In traditional Shotokan karate kihon, this is typically done in a static front stance. This is fine for isolating hip and shoulder movement for a beginner yet it is still practiced this way by advanced black belts.

The author demonstrates a static vs fluid punching combination.

You can’t fight with this robotic movement so I believe this sort of training should be limited. In my curriculum, white belts must perform this combination for their 8th kyu test. They start from a more natural fighting stance. To my knowledge, this is not done in most Shotokan organizations until the nidan test. Why? Why wait so long?

Beginner students are shown performing kihon during their 8th kyu test.

6. Kihon is too Linear. Shotokan kihon tends to be very linear. Having trained in 3K Shotokan for many years, I have never seen an instructor teach an effective hook punch, or kage zuki. Usually, it’s demonstrated as seen in the Tekki katas, from a kiba dachi and using hikite. It’s very much a neglected technique, likely due to the influence of competition. It is difficult to throw a hook punch with control in a non-contact match. Competition often drives instruction and so what doesn’t work in competition unfortunately gets discarded.

Neglecting circular techniques such as kage zuki only limits our growth. In my syllabus, the hook punch is first seen at the 8th kyu level. Yellow belts must demonstrate a kizami/gyaku/kage zuki (jab/cross/hook) combination. For a lead hand hook, the front heel must come up.

The authors’ students working a kihon combination on the pads which is found in his 7th and 6th kyu kihon curriculum.

7. Lack of context. Context is key. Without it, we fail to have any real purpose in kihon training, other than getting good at kihon. Remember, good kihon is a tool, not a goal.

Without context, kihon it is nothing more than a workout. Again, if that’s all you are looking for in karate then by all means, keep punching those air molecules. For me, however, that’s not enough. Consider the following combination that I had to do for my nidan in 1994; step back knife hand block in back stance, front leg kick, spear hand strike with the rear hand while staying in back stance. Never in all my days has an instructor demonstrated a practical application for this. There’s a simple reason for this. Many of the kihon combinations we see in Shotokan syllabi are just a random collection of techniques for the development of body movement. They are void of context.

The author demonstrating a typical kihon combination found in traditional Shotokan.

In January, 2020, I left my Shotokan organization and joined the World Combat Association. When I was writing my curriculum for the WCA, I had a conversation with Iain Abernethy. I was really struggling with how to make kihon meaningful. I had no interest in continuing with the dysfunctional JKA type of kihon I learned. Iain spoke about pairing kihon with pad drills and partner work and so that’s exactly what I did. I now had context for my kihon. I had already decided which pad drills to do for each kyu level. I simply turned the pad drills into solo exercises for kihon.

Not everybody practices karate for the same reasons. You could use this approach for a variety of contexts; close range striking with punches and elbows, kicking techniques, long range sport karate. It is very adaptable because it’s just good common sense.

Note the footwork in the video below. The stance starts higher and a type of karate footwork called yori ashi is used for the first two punches. The chin is slightly tucked and the non-striking hand is held in a guard rather than pulled to the hip. The rear heel is allowed to raise naturally. Practicing kihon in this manner promotes good habits in the beginner; keeping a guard, functional footwork and fluidity of movement. There is no “unlearning” of bad habits as the novice advances up the ranks. As a side note, this kizami zuki/gyaku zuki/kage zuki (jab/cross/hook) combination is part of the testing requirements for my students testing for 7th and 6th kyu. The perform the solo kihon combination and its application on focus pads.

The author demonstrates a functional kihon combination that can be applied to a target. This combination is in the author’s 7th and 6th kyu curriculum.

Conclusion

It truly baffles me when karateka of 30+ years experience go on the “BASICS BASICS BASICS!” rant. Many will insist that it’s the most important part of training. I could not disagree more. Basics are, well, they’re basics. They are a starting point.

I personally don’t practice the traditional variety of kihon anymore. It’s not that I think I have perfected it. It’s just I realized long ago that there comes a point of diminishing returns. I no longer worry about forcing my body to conform to the arbitrary aesthetic standards associated with 3K karate especially now that my body is aging. I could keep trying to generate “snappy” techniques because they helped me win tournaments in the past or I could work on hitting a target with greater impact. As I write this, I am closing in on my 50th lap around the sun. Regardless, I hit harder than when I was in my prime at 35 despite the fact that I have lost a lot of speed, muscle mass and flexibility. I train differently now. Medals are no longer a priority.

Letting go of the traditional kihon was difficult for me when I was developing my curriculum. It had been part of my training for 30 years. I had to remind myself that the ‘line training’ that is so popular in Shotokan dojos was never meant to be practical and so it was more of an hindrance than an aid to learning functional mechanics.

Some people have told me that their kihon develops fitness, speed, coordination and mind development. I won’t argue with that but these outcomes should be a natural side benefit of practical training. Impractical kihon will not result in sound fighting or self defense skills. Practical training can develop fitness, speed, coordination and mind development.

Anybody wishing to make their teaching/training more functional should consider modifying their kihon. Granted, if you are in a 3K organization, you’ll still have to teach the “grading kihon” for testing purposes but contextual kihon will add a nice balance.

Remember, Good kihon is a tool, not a goal.

Thanks for reading!

Andy Allen