Karate: A Call for Change

“Times change, the world changes, and obviously the martial arts must change too.”

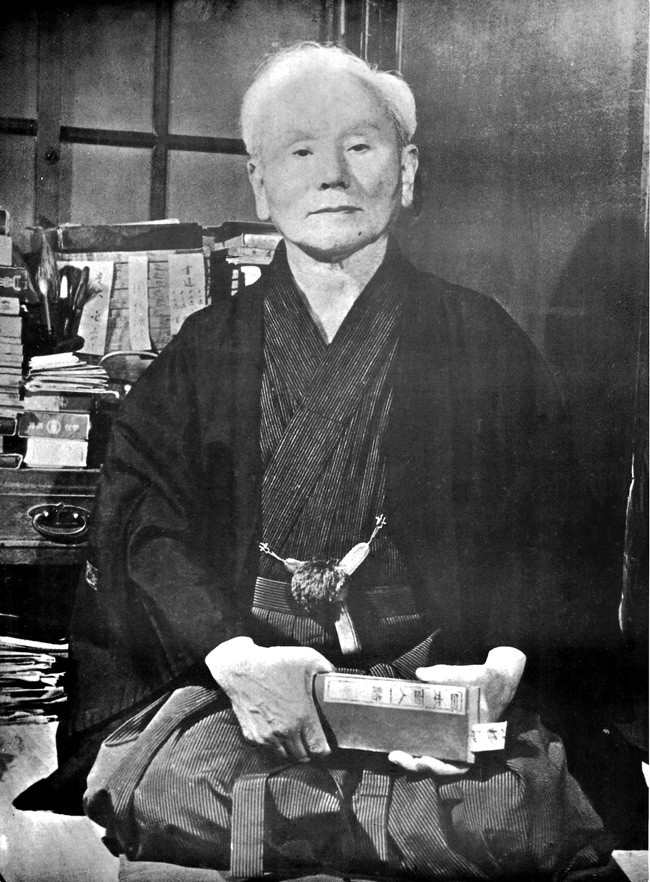

~Gichin Funakoshi

By Andy Allen

It has been said that change is the only constant. In nature, species evolve as a means to ensure survival. Failure to evolve ends in extinction.

Karate has undergone a massive transformation from its pre-Japan roots. What has become Shotokan karate is the result of evolution. Much like organisms change over time to adapt to their environment, so too has karate. Failure to adapt would have resulted in its extinction but the changes that occured in the early to mid 1900s came at a cost.

Evolution is a funny thing. In nature, a mutation that puts an individual at an advantage has a greater chance of survival and, thus passes its genes on to the next generation. Take the peacock for example. The male has evolved a spectacular display of tail feathers. It seems as though at some time long ago, the lady peacocks started digging guys with pretty tails. The guys with the biggest and boldest tails were rewarded with female companionship while the dull looking dudes stayed home and wallowed in self-pity.

So, what does this have to do with karate? Well, much of today’s karate is like the male peacock. It’s very pretty to look at but isn’t all that functional. It was years ago that I started to question why we, as Shotokan practitioners, put so much emphasis on ‘correct’ form. All the various instructors I trained with over the decades had similar teaching points regarding posture, body alignment, strong stance and how to generate more power (albeit without actually hitting anything). It was always rigorous training but it was often done without making any physical contact with another person.

One thing few people seem to understand is that in karate training there are two types of form and they are not the same thing; there is form for function and form for… well… feather grooming. The peacock is stunning to look at but it’s pretty defenseless. That wild dog will quickly grab it by those long tail feathers and drag it home for supper! Likewise, pretty kata meant for competition is good for… well, it’s good for looking pretty.

The funny thing about evolution is that it doesn’t always work out for the best both in nature and in martial arts. The peacock’s feathers are an obvious issue when evading predators, the bull moose’s giant antlers make navigating through the brush cumbersome and giraffes give birth standing up. Sure, being tall has its advantages but that’s a 1.5m (5’) drop! Welcome to the to the world, baby Johnny. Ouch, want some ice for that?

At this point, my words are either resonating with you or I am ruffling your feathers (see what I did there?). Today’s Shotokan has its strengths but those strengths are outweighed by its limitations.

Okay, let’s get to the point already! Karate, perhaps one of the earliest mixed martial arts, was once a complete system of self defense. It not only included percussive impact, but also a variety of throws, chokes, joint locks, use of pressure points and even ground work. Although there are styles that practice some of the above mentioned techniques, this is all but lost in the Shotokan world. It has become a watered down punch/kick/block system more geared towards recreation and sport than for self defense.

Individual teaching styles aside, a quick survey of the syllabi of all the large Shotokan organizations will reveal that Shotokan is not a suitable avenue to pursue in search of an effective self defence system. Entrenched in 3K (kata, kihon and kumite), the core of Shotokan is focussed more on the pursuit of aesthetically pleasing movements than self protection (insert peacock analogy here). The only partner work included in a test is some type of kumite. The step-sparring (gohon, sanbon, ippon kumite) teaches dangerously bad habits and jiyu (free) kumite is often reserved for those testing for nidan or higher. Jiyu kumite has evolved from a sport karate model and has no resemblance to the skills required for self defense. None of the syllabi address Habitual Acts of Physical Violence, the purpose for which karate was originally intended. There is no requirement for demonstration of practical skills; impact into actual targets, throwing, locking, choking, ground work or realistic kata application. Just show off your plumage!

The shodan Shotokan practitioner who only trains for the testing syllabus is ill prepared to protect themselves in a physical altercation. The syllabus is simply too shallow and lacking in so many skill sets. There are many reasons for practicing karate but developing reliable skills for self protection should always be a priority. After all, karate is a martial art.

The practical karate movement has been gaining momentum and despite what I read from someone in a popular karate publication, it’s much more than a fad. So called ‘traditional’ karate is broken. A strict ‘form over function’ approach will not save your life. Perhaps you have had an encounter with another martial artist who trains in a hands-on art like jiu jitsu, judo or muay thai. Try showing them the shodan grading syllabus from your organization and ask what they think. You won’t like their answer. But wait, before you shrug them off and lament, “Well they just don’t understand traditional karate”, go spar or grapple with them.

In the pre-Japan era, karate in Okinawa was a brutal, holistic and complete martial art. Today’s karate would surely be unrecognizable to the founding masters. Even the late Gichin Funakoshi wrote, rather sorrowfully, in his second edition of Karate-Do Kyohan that he was dismayed at the changes seen in karate.

“Although one might claim that such changes are the natural result of the expansion of karate-do, it is not evident that one should view such a result with rejoicing rather than with some misgiving.”

So how did we get here? The answer is evolution. Like the peacock, however, evolution results in beneficial developments but sometimes is accompanied by attributes that will eventually lead to its demise. Let’s look a little further back.

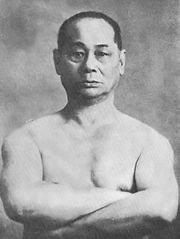

In the early 1900s, Anko Itosu, the grandfather of modern karate, was teaching karate in the Okinawan school system. The Pinan katas were taught (we call them Heian in Shotokan) as a form of physical education. However, the school-based karate was much different than the usual karate he taught. He did not teach the applications for throws, joint locks and chokes as that was not appropriate for school children. Instead he only taught the movements of kata.

In 1908, Itosu wrote his famous letter to the Japanese Ministry of War and the Ministry of Education in a pitch to make karate part of the educational system in mainland Japan. In the second of the ten karate ‘lessons’, Itosu writes,

“The primary purpose of karate training is to strengthen the human muscles making the physique strong like iron and stone; so that one can use the hands and feet like weapons such as a spear or halberd. In doing so, karate training cultivates bravery and valor in children and it should be encouraged in their elementary schools. Don’t forget what the Duke of Wellington said after defeating Emperor Napoleon, “Today’s victory was first achieved from the discipline attained on the playgrounds of our elementary schools.’”

It was the children’s karate that was pitched in Japan, It was meant to instill obedience and develop strong minds and bodies. This was the beginning of the transformation of karate from a ‘jutsu’ to a ‘do’ martial art and into what I would consider to be ‘modern’ karate.

Funakoshi recognized that if he was to be successful in popularizing karate in Japan then he would need to teach karate differently than how he was taught. In his book, ‘Karate-Do, My Way of Life”, Funakoshi writes,

“Hoping to see Karate included in the universal physical education taught in public schools, I set about revising the kata so as to make them as simple as possible. Times change, the world changes and obviously the martial arts must change too.”

I think there are lessons to be learned here. Both Itosu, and later, Funakoshi recognized that if karate was to survive, sacrifices had to be made. It was the children’s karate that flourished in Japan and later evolved to what it is today; a declawed version where aesthetics are valued over functionality for a self-defense context. Form over function. Remember the peacock? Times had changed. The world had changed and obviously karate had to change too. There was little no place in Japanese society for the brutality of Okinawan karate. It needed to evolve to conform to the Japanese ‘do’ ethos.

Now, nearly 100 years after the introduction of karate to Japan, I believe things are coming full circle. The practical karate movement has been making waves for a number of years now. Western culture does not do well with the conformist culture of Japan so it’s no surprise that the practical karate movement is a western initiative. We like to ask questions and we want answers.

3K karate is somewhat of a dinosaur. So this begs the question; why are so many people so hell-bent on ‘preserving’ 20th century karate like some prehistoric mosquito in amber? Tradition? The old masters never meant for karate to be preserved…to remain unchanged.

With various mediums of social media, the general public of today has a much greater ability to distinguish impracticality from efficacy in martial arts. There are many reasons for practicing karate today but as I have previously stated, I believe that training must be functional. Motobu said, “Nothing is more harmful to the world than a martial art that is not effective in actual self-defense.” What would he think of today’s karate that is so far removed from what he and his contemporaries learned?

“Times Change, the world changes and obviously the martial arts must change too.” It’s time for karate to evolve…again.

Andy Allen

Work Cited:

Iainabernethy.com

karatebyjesse.com

Tanpenshu by Patrick McCarthy